The Nahr El Kalb, or the River of the Dog is surrounded by two rocky promontories which face each other, separated by the valley where the river flows, forming a natural obstacle on the coastal road.

The massive rocky promontories have preserved the names, titles and sometimes figurines of sovereigns who have had an inscription or a relief engraved in their names.

Purpose

The difficulty of the passage is initially put forward to explain the presence of the first sculpted reliefs.

Evoking the valley of Nahr El Kalb, French author Guerin emphasizes that “the difficulty of crossing this course where a small number of brave defenders could stop an entire army, making glorious the passage, where several of the conquerors who accomplished it took the honor to point out in this very place this fact to prosperity by means of inscription and bas-reliefs”.

Toponym

The River of the Wolf or Flumen Lycos is mentioned by Pliny of elder “It is the Lycos of the Greeks, the Lycus of the Romans, that is to say the River of the Wolf, the Arabs by translating this name, made it the River of the Dog”.

Several author and travelers of the 16th and 17th century such as Jean de Thevenot and Vinvent Stochove announce that an idol in the form of a dog would have been erected at the top of the southern promontory, and that this idol gave oracles, and barked when conquerors approached of the promontory.

The French author Laurent d’Arvieux took up the legend that a statue of a dog at the top of the cape of Nahr el Kalb emits loud barks that can be heard as far as Cyprus. He goes on to point out that the Turks knocked down the statue and threw it into the sea.

Other travelers are more skeptical and refute the correlation between a statue and the name of the river. The subject of the name given to the river remains debatable.

Importance

The reliefs and inscriptions which extend from the 13th century BC and the beginning of the 21st century AD make the valley of Nahr el Kalb a unique open-air museum. This one-of-a-kind site brings together in one place the witnesses of certain events that marked the region.

No similar site, which has saved inscriptions from such diverse periods in a common location, is known to-date.

Franz Heinrich Weissbach, the first editor of the inscriptions in 1922, points out: “chronicles on stones, of incalculable value”.

French author Paul Mouterde points out “It was the destiny of Lebanon, crossroads of three continents, and meeting point between civilizations, that to awaken the convoys of the most powerful empires, from the long vicissitudes of its history the rocks of Nahr El Kalb keep a strange reflection”

The Dog Statue

A courier dated on July 11th 1942 preserved at the General Directory of Antiquities talks about an antique statue with a missing head was found in the sea below the cap of Nahr El Kalb by the Australian company who was working on the railway.

The New York Times published an article dated August 6th 1942 titled “Ancient Statute Is Uncovered in Lebanon: Stone Wolf Once Guarded Narrow Pass”. The article talks about a well preserved antique statute with a missing head which will be conserved at the National Museum of Beirut.

The statute would later disappear without a trace from the National Museum’s storage.

Languages & Writings

The rocks of Nahr El Kalb bear eight different languages:

Egyptian, Assyrian/Neo-Babylonian, Latin, Greek, Arabic, French, English and Turkish.

There are three types of writing which give each inscribed bas-relief its own specificity:

Hieroglyphic, the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt

Cuneiform, a logo-syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East and

Alphabetical, a standardized set of basic written symbols or graphemes that represent the phonemes of certain spoken languages.

Reliefs and Inscriptions

21 reliefs and inscriptions are found on the Southern promontory of Nahr El Kalb, and 1 on the northern side:

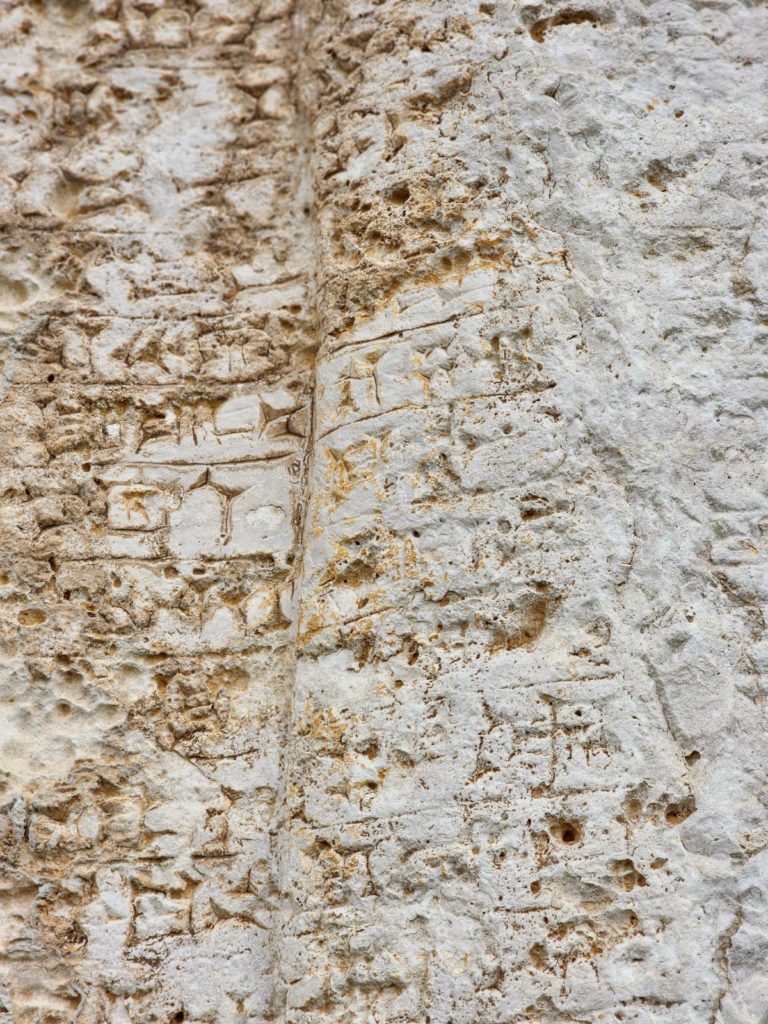

Egyptian reliefs

Stele #14, dated between 1279 and 1213 BC, representing the relief of God Re-Horakhty and Ramses II

Stele #16, dated between 1279 and 1213 BC, representing the relief of God Amun Re and Ramses II

Unnumbered stele – this stele has been replaced by another in the name of Napoleon III. The original stele depicted the god Ptah facing Ramses II.

Assyrian Reliefs and Inscriptions

Stele #6, dated around 1140 BC, representing the relief of Assyrian king Ashur-ris-ilim

Stele #7, dated around 1100 BC, representing the relief of Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser I

Stele #8, dated around 885 BC, representing the relief of Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal

Stele #13, dated around 860 BC, representing the relief of Assyrian king Shalmaneser III, along with divine symbols.

Stele #15, dated around 705 BC, representing the relief of Assyrian king Sennacherib, along with divine symbols.

Stele # 17, dated between 681 and 671 BC, representing the relief f of King Esarhaddon, mentioning his victorious campaign in Egypt.

Inscription #1, dated between 605 and 562 BC, 2 inscriptions of king Nabuchednezar II, one written in old Babylonian and the second in neo-Babylonian, mentioning the construction of Babylonia’s city walls, temples and lagoons. The remaining important portion of the texts vanished due to erosion.

Greek and Latin Inscriptions

Inscription #3 – Latin, dated between 211 and 217 AD, in the name of Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (known as Caracalla) mentioning the works of developing and maintaining the Roman road around the promontory.

Inscription #11 – Greek, dated between 382 and 383 AD, in the name of Proculus, Roman governor of Palestine and Phoenicia, mentioning the works of fixing a passage around the promontory.

Inscription #12 – Greek, unknown date and purpose.

Arab Inscriptions

Inscription #2, dated between 1384 and 1389 AD, engraved on the rock opposite of the Barquq Bridge, mentioning the restoration of the bridge under the reign of Sultan Al-Malik Az-Zahir Sayf ad-Din Barquq by the order of Emir Aytmish Al Bajasi.

Inscription #18 (A-B) , dated in 1901, with 2 identical inscriptions facing each other on either side of the Ottoman bridge, engraved with Arabic cursive writing for stele A and old Turkish writings for stele B, mentioning the construction of the bridge under the reign of Sultan Abd El Hamid II.

Stele #21, dated December 31, 1946, includes an inscription commemorating the evacuation of all foreign troops from Lebanon during the reign of President Bechara El-Koury.

Stele #22, dated May 24, 2000, mentioning the liberation of Lebanon from the Israelis.

French Inscriptions

Inscription #2, dated in 1961, mentioning the battalions who intervened in Lebanon under Napoleon III following the Christian-Druze conflicts in Mount-Lebanon.

Inscription #4, dated in July 25, 1920 mentioning the victorious entry of the French army into Damascus.

English Inscriptions

Inscription #9, dated in October 1918, mentioning the battalions which took part in the battles of Damascus, Homs and Aleppo and liberating the cities from Ottoman rule.

Inscription #10, dated in October 1918, mentioning the battalions that liberated Beirut and Tripoli from Ottoman rule.

Inscription #19, dated in June-July 1941, mentioning the Australian, British and French battalions that liberated Lebanon and Syria from the Vichy government during the 2nd world war.

Stele #20, dated in December 20th 1942, mentioning the completion of the Beirut – Tripoli railway. The stele of this inscription is today isolated between the tracks of the Beirut – Jounieh motorway.

Additional Monuments

The Roman aqueduct: probably dating to the 3rd century AD. The aqueduct was extended by Emir Haidar Chehab at the beginning of the 18th century to water the cultivation fields located on the coast.

The statue’s foundations: the presumed foundations of the dog statue from which the ottomans dismantled and throw the edifice into the sea.

The obelisk: a yellowish limestone monument that commemorates the martyrs of French soldiers. The obelisk was erected on the Avenue des Francais in Ras Beirut during the 1950s, then it was relocated to Nahr El Kalb in 1960.

Pre-historic cells: From prehistoric times, man found refuge at the foot of the promontory. Three rock shelters, two of which are still partially preserved, in fact hosted human groups at different times, during the Middle Paleolithic (100,000-70,000 years BP (Before Present), the Chalcolitic (4th millennium BC) and the Bronze Age (3rd millennium BC).

Scroll down to enjoy the pictures and to locate the site on the map.

Karim Sokhn

Tour Operator & Tour Guide

References:

BAAL Hors-Serie V

http://www.lorientjunior.com/article/1346/les-pepites-archeologiques-du-site-de-nahr-el-kalb.html

*Acknowledgment to Karl Azzam, Archeologist